'90s Rewind: How Point Break and Kathryn Bigelow Made Waves in 1991

It's that place where you lose yourself and find yourself.

Throughout the 1980s, American action films were notoriously steeped in masculinity and machismo, with the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone and their unbelievably chiseled physiques becoming the benchmarks for our cinematic heroes of that era. As the decade wore on though, there was a transitional period in action filmmaking, with the success of movies like Die Hard and Lethal Weapon or Michael Keaton taking on the role of Batman, this late ‘80s trend proved that “regular” guys could play the hero too, and that audiences would still show up in droves.

And even though those films have been recognized for this new trajectory in action movies, another game-changer in the realm of action came along a few years later in the form of a philosophical story about an F.B.I agent who has to infiltrate a group of surfers in order to stop an ongoing string of bank robberies happening all around Los Angeles, and he finds himself questioning everything about what he believes in after being deeply drawn in by the group’s enigmatic leader.

That movie was Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break.

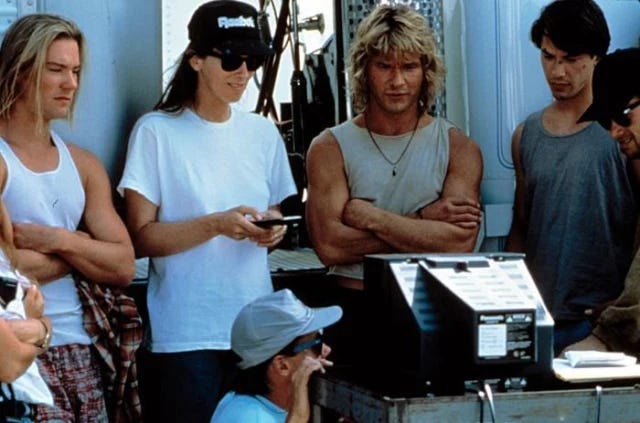

It was in the early 1990s when Bigelow was brought on to take the helm of Point Break, at the behest of her then-husband James Cameron. That was a decision that would not only change the direction of Bigelow’s career, but it also had a huge influence on the subsequent careers of Point Break co-stars Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze as well. Beyond that, Point Break also challenged audiences’ expectations of what American action filmmaking was all about by crafting a movie that broke down gender stereotypes, and also delivered one of the most introspective and lyrical actioners to have ever graced the silver screen.

Even from very first moments in the film, Point Break demonstrates a strong female gaze, as Johnny Utah (Reeves), dripping wet in a form-fitting t-shirt, slowly pops a stick of gum into his mouth and sets out to pass a shooting test with flying colors. That sequence is intercut with slow-motion footage of a magnetic surfer named Bodhi (Swayze), careening through the waves, almost hypnotically (and maybe even a little seductively), as a means for enticing viewers to immerse themselves in his world.

From there, the first occurrence of nudity in Point Break happens early on, during the opening bank robbery when one of the “Ex-Presidents” bears his ass to a surveillance camera, with the words “Thank You” defiantly scrawled across both cheeks. Very rarely in action filmmaking do we see male stars treated with this kind of manner, but turning conventions on their head has always been Bigelow’s greatest asset as a director, with Point Break being yet another example of her deft ability of challenging cinematic conventions, but also, still creating something that could be appealing to mass audiences.

With Point Break, Bigelow also takes on the concept of female nudity in cinema and transforms it into a moment of empowerment. During the scene when Utah, his partner Pappas (Gary Busey), and their fellow agents Alvarez (Julian Reyes) and Babbit (Daniel Beer) conduct a raid on the house of a ragtag group of extreme surfers, led by Bunker Weiss (Chris Pedersen), initially we see the silhouette of a nude female form showering in the background.

As chaos breaks out, with guns blazing and tensions running high between all the male characters in the sequence, the most badass moment in the raid happens when that nude woman from the shower, who also happens to be named “Freight Train” (played by Road House’s Julie Michaels who is an amazing stunt performer all-around), decides she’s not ready to play victim while the FBI terrorizes her cohorts.

Freight Train, nearly unfazed by the fact that there’s shoot out happening in her midst, is aggressively angry with Utah over this intrusion, and kicks the ever-loving crap out of Reeves’ character, first smashing him into a mirror, and then dropping him to his knees after a series of ball-crunching blows. Rather than take a moment to grab a towel, Michaels’ character isn’t satisfied with the destruction she’s wrought, so she sets out to stab Babbit repeatedly in the back, too, all while fully nude, before Pappas finally knocks her out.

Generally, the inclusion of female nudity in action movies during this era in cinema was utilized to titillate viewers (one could call that the “Joel Silver Rule”). But in Point Break, Bigelow reconstructs what could be considered an exploitative moment into something far more powerful – one that leaves the film’s hero gasping on the floor, proving that Utah was totally out of his element (which is a running theme for the overachieving FBI agent).

Of course, the biggest example of how Point Break challenged traditional male/female dynamics in action storytelling is reflected in the relationship of Utah and Tyler Ann Endicott (played by the amazing Lori Petty). Once Johnny learns that it’s a group of surfers behind a series of bank robberies, the former Ohio State football star sets out to teach himself how to surf at the instance of his partner. Utah initially scoffs at the task (“Surfing is for little rubber people who can’t shave yet”), but as he sets out in the water, Utah finds himself immediately out of his depth – pun intended.

Utah ends up getting pulled into an undercurrent, quickly losing his battle with the waves as they swallow him whole, and in this moment, the up-and-coming agent is once again getting his ass handed to him by something that he completely underestimated due to his own sense of superiority.

Out of nowhere, a very annoyed Tyler rescues Utah, all while chastising him for his lack of experience in the water and ridiculing his enormous surfboard to boot. Also, this is just a sidebar, but I love that an ongoing motif in Point Break is women who are fed up anytime they are inconvenienced by men who act like idiots because that just rings so true on so many levels.

But even though Utah is the one who initially manipulates his relationship with Tyler into existence, she’s the one who always maintains control throughout Point Break. The most obvious example comes from the montage of Tyler teaching Utah how to surf, as she’s seen standing tall, all while barking orders down at him in the sand. But this dynamic carries over throughout the rest of the film, too.

During the house party scenes at Bodhi’s, there’s a moment when Tyler declares, “There’s too much testosterone here,” and walks away. Without being prompted, Utah immediately follows behind her, demonstrating the power that Tyler already wields over her surfing protégé, and they haven’t even been intimate at that point in the film.

The football scene in Point Break is also another fantastic showcase for not only Petty’s dynamic performance in the film, but also how her character fits into this usually male-dominated realm that’s brimming with friendly competition and a smidge of bromance. Tyler is tossing around the pigskin right alongside all of the boys here, even mocking them at one point when she scores, proving that she’s just as capable of being a badass as they are.

There’s also the confrontation scene that happens in the latter half of Point Break, when Tyler realizes that Utah has been lying to her all along. As he lies sleeping in bed, Tyler discovers the FBI agent’s secret, and brandishes his gun (an obvious phallic symbol), getting off a single shot near his head while Utah obliviously rests, unaware of the danger he’s in. As she emotionally interrogates Utah, Tyler is in a state of undress, only revealing the curvature of her body that’s hidden in the shadows and underneath a precariously positioned dress shirt. Once again, Utah finds himself getting pummeled by a nude woman, only this time it’s an emotional asskicking that he’s on the receiving end of, and what’s remarkable is that there’s nothing particularly sexualized about this moment either.

With Point Break, Bigelow examined a rare intimacy shared between male characters in a way that had never been addressed before by a mainstream action film before, and also challenged gender norms in action cinema by demonstrating that in many cases, a man’s worst enemy is himself, or more specifically, his ego. Throughout her career, Bigelow has always been a rule breaker behind the camera, but when it comes to Point Break, she established her own set of rules.

Not only did the filmmaker create new storytelling precedents in a world where women were in often in control, especially when it came to their sexuality, but Point Break itself felt like a defiant cinematic declaration saying that it was now okay for male characters to connect with each other on a much deeper level than we had seen previously in films of the same ilk.

Beyond that, Bigelow also happily obliterated the concept of gender norms with her work in Point Break, which feels like a revolution in and of itself, as she was working in an arena where female storytellers never really had an opportunity to have a seat at the table before.

During the scene when Bodhi is proselytizing to his surfing buddies in Point Break, he declares, “It’s us against the system.” With that moment, Bigelow, in her own way, was boldly challenging the constructs of action-oriented storytelling through her work in Point Break, and the genre was forever changed in its wake.