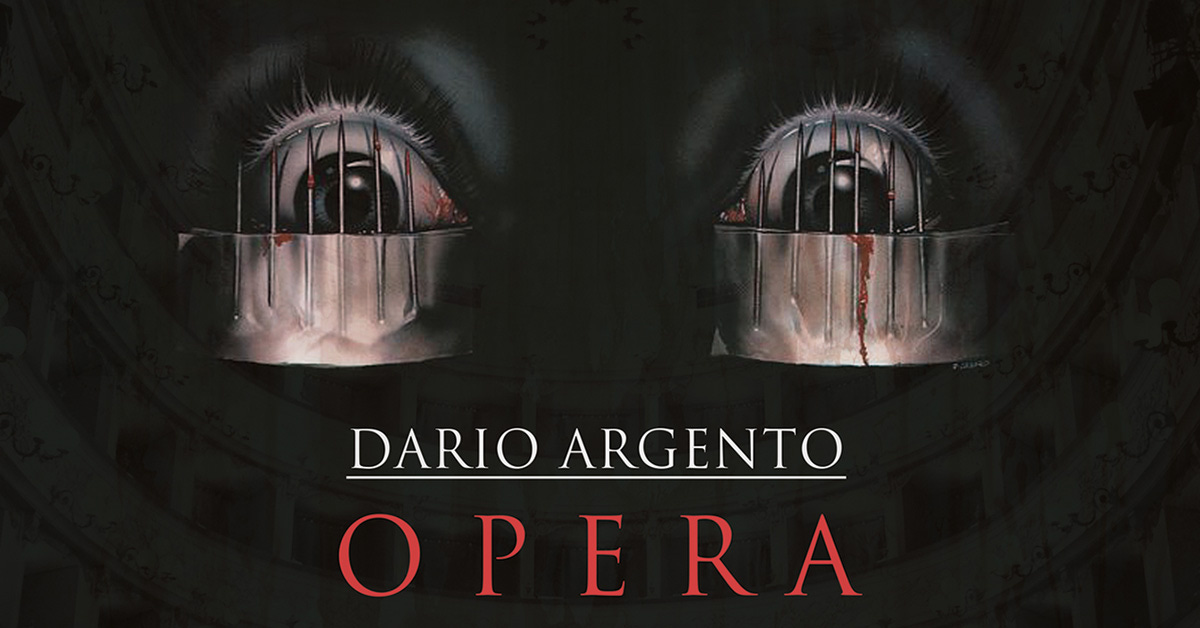

Phantom Thread: Dario Argento's Opera

This time, our director OD’d on weird. It isn’t like the movies.

For this installment of Phantom Thread, I decided to pay tribute to one of my favorite films from my favorite Italian filmmaker, Dario Argento. But instead of writing about his 1998 adaptation of Phantom of the Opera (which I do enjoy, even if it’ll never make my list of favorite Argento movies ever), I thought it would be fun to first dive into his 1987 manic masterpiece Opera for this entry in my ongoing series on Phantom-adjacent entertainment.

As it turns out, Opera is a film that I will never get tired of writing about, as this is my fourth piece on the film, although I do think Tenebrae is the only Argento movie I’ve written about the most so far in my career (two podcasts and five articles).

But what makes Opera so unforgettable is how Argento manages to create an inescapable waking nightmare of violence and voyeurism with his work here that could also be considered one of the Maestro’s most unapologetically philosophical and introspective entries in his entire filmography to boot.

Throughout Opera, Argento boldly toys with Giallo conventions in a variety of unique ways, often blurring the lines between reality and imagination, and examines the effects of trauma that haunt both Opera’s protagonist and antagonist alike. It’s also an endlessly fascinating take on the dynamics at play in Gaston Leroux’s original 1909 novel that puts a new spin on this timeless story about the detrimental nature of creativity and how our obsession with popular culture threatens to consume the very fabric of our humanity.

Go back to horror films. Forget opera.

Even though Opera feels very much in line with Argento’s sense of style as a visual storyteller, there’s something incredibly singular about his approach to his cinematic clash of high art and Giallo-infused hysteria. While there is certainly a mystery that propels the film’s narrative, one involving an up-and-coming soprano named Betty (Cristina Marsillach), who finds herself taking on the role of a lifetime in a bold, revisionary opera production on Macbeth from horror film director Marco (Ian Charleson), who may have bitten off more than he can chew.

Between the battle-worn sets, back projection, and a murder of unruly ravens, Marco clearly is looking to make his creative mark on a world he doesn’t necessarily fit into, and Betty’s lack of experience leaves her feeling just as daunted as her director, unsure if she’s truly ready to step into the spotlight. But there is someone who believes in Betty—an unknown entity who fantasizes about her, and makes the burgeoning singer the centerpiece of his deadly murder spree.

And as the body count surrounding Marco’s production begins to rise, it’s up to Inspector Alan Santini (Urbano Barberini) and his partner Daniele Soavi (played by director extraordinaire Michele Soavi) to try and stop the killer’s reign of terror once and for all.

Betty’s journey is front and center in Opera, but I find Marco’s story arc in the film extremely fascinating, as it clearly feels like Argento is using the character to project his own insecurities and work through some real-life creative frustrations throughout this story. There’s an intimacy to the filmmaking in Opera, between the role of Marco as well as how up close and personal the camera often gets throughout the film, resulting in an experience that is as vulnerable as it is horrifically unsettling.

It is worth noting that at one point in his career, Dario was set to make his own version of Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto, but his take was deemed “too violent” and production was canceled in the mid-1980s. That led to Argento working on the script for Opera for several years out of professional frustration.

And there’s no denying that those real life circumstances are why Opera feels like Argento’s most personal film, with him utilizing the character of Marco — a horror director who feels like the world has deemed unworthy to be at the helm of a prestigious creative endeavor like an opera — as his very own cinematic avatar, there to represent his own frustrations as an artist at this point in his career.

It’s no secret that while most people will watch horror movies, many of those very same folks will dismiss them as “lesser” art forms, and I think the way that these two worlds collide in Opera is unapologetically Argento in every way.

For every gorgeously composed moment we see of the Macbeth live performances inside the stunning Teatro Regio di Parma opera house, in turn, Argento delivers up a merciless and savage death, subjecting the film’s protagonist Betty to endure every blood-soaked hack and slash. There’s no escaping the carnage — from brutal stabbings to throats being ripped out to an innovative peephole gunshot kill — and Argento wants to make sure that we bear witness to everything he has in store for us, much like Opera’s protagonist Betty, who the masked killer outfits with a strip of needles below her eyes, making it impossible for her to look away.

You’ll just have to watch everything.

In the first murder scene that Betty finds herself helplessly forced to watch in horror while the killer attacks her boyfriend, Stefano (William McNamara), she’s tied to a pillar, with her mouth covered in tape, and the assailant has taped a row of small needles just below Betty’s lower eyelids. Before he attacks Stefano, the killer warns Betty that if she dares to close her eyes, her lids would be shredded as a result, which forces the innocent ingénue to bear witness to the grisly and unflinching violence as it unfolds.

Once he’s finished, Stefano’s executioner allows Betty to go free, but doesn’t provide a reason behind his unexpected decision. This is definitely a change-up from the dynamic between the Phantom and Christine Daae in the original Phantom story. In Leroux’s tale, the ingenue’s benefactor hides his dastardly deeds from his lady love and works within an aura of mystery. In Opera, Betty is forced to watch every horrible act as it unfolds, as a penance of sorts, as the killer wants to push her to the brink of sanity, instead of supporting her breakout moment in her career.

But the masked killer uses this confrontational technique once again when he attacks Guilia (Coralina Cataldi-Tassoni), the seamstress, who happens to stumble upon a clue to his identity the next day. After she discovers a mysterious bracelet entangled in Betty’s costume, Guilia realizes there’s a worn-down inscription on it, and figures out that it must tie into the murderer’s motivations. But before Guilia can fill Betty in on her discovery, the young singer is once again held against her will.

This time, the songstress is placed inside a costume display case, with the killer once again mandating that she is to observe his merciless actions, which involve removing the bracelet that Guilia swallows by cutting a hole in her throat so that he can retrieve the incriminating jewelry. Before he leaves, the killer subtly reminds Betty of the power he holds over her, pushing the scissors close to her abdomen as a warning before he sets her free.

Regarding the intimate nature of Opera’s filmmaking, the greatest example of that comes during the innovative death scene of Mira (Daria Nicolodi), Betty’s agent who makes the unfortunate mistake of looking through a peephole at the worst possible moment. It’s a shocking, ghastly moment in Opera, and it might just be one of the greatest cinematic deaths that Argento has ever concocted in his career (which is saying a lot when you consider just how impressive Argento’s efforts have been whenever it comes time to bid one of his characters adieu).

By having her character as a witness to these vicious crimes, Argento makes Betty, and ultimately us as the viewers, complicit in these murders. It’s a masochistic approach that serves Opera well, especially since it feels like the director is also challenging himself and his use of violence as a storyteller here as well. Opera is about the observation and fetishism of the inhumane acts that we commit against one another, and through a series of flashbacks, Argento lays out just exactly why Betty has been chosen by the killer. It’s because, even as a child, Betty has always been surrounded by acts of cruelty, malice, and rage, and we see how that trauma nearly consumes her all these years later, and ultimately leads to the death of the homicidal perpetrator during Opera’s epilogue, too.

Again, this is very different from the character dynamics in Leroux’s story, where Erik, the Phantom, is the one who is surrounded by acts of cruelty due to his deformity. Christine has been haunted by this entity since her childhood (although, interestingly, there is a maternal figure at the core of both these stories), and this “Angel of Music” only ever acts out of his love for her and her voice.

I can’t decide whether it’s just a dream… or the memory of something that really happened.

Opera also seamlessly blends elements of the real and the imaginary, which are heightened by Betty’s confusion and paranoia. She’s often an unreliable narrator in the film, despite the fact that she’s in attendance for most of the deaths (barring the stagehand who meets the pointy end of a hook during her first onstage performance). We’re left wondering just what exactly is going on after Betty confides in Marco that what’s been happening to her somehow connects to these nightmares she’s had ever since she was a child. There are numerous shifts in time and place throughout Opera, leaving viewers to try and figure out just where exactly the Maestro is taking us on this particular cinematic journey.

Argento and his cinematographer Ronnie Taylor do a fantastic job of keeping viewers guessing throughout Opera. By often changing the first-person POV camerawork to represent different characters’ perspectives, it plays up the mystery at the center of the story, and allows Dario to push boundaries in ways he hadn’t really attempted before in his career. But there’s no denying that Opera is a breathtaking visual feast due to Taylor’s efforts who also lensed Sea of Love, Popcorn, and oddly enough, Argento’s Phantom during his career, and utilized his talents as a camera operator on films like Ken Russell’s The Devils, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, and Phantom of the Paradise.

In Opera, Taylor finds a lot of innovative uses for his Steadicam, where sometimes the camera moves throughout different scenes like a frenzied whirling dervish during some of Opera’s chase scenes (that spiral staircase scene — MY GOD). In any case, Taylor does some incredible work on the film on a technical level that is truly next-level, and it absolutely heightened the tension and terror that Argento is continually building throughout Opera’s various set pieces.

We even experience the POV of the ravens being utilized in Marco’s avant-garde interpretation of Macbeth. Beyond the fact that it allows for some dazzling camerawork, this bird’s eye view becomes a crucial element in Opera’s audacious reveal, where the ravens expose that it was Santini who had been behind Betty’s ongoing torment and the series of grisly murders as well. Honestly, the raven attack scene is a totally batshit, yet utterly brilliant, sequence from a cinematic madman and his trusty DP who was willing to go the distance in order to deliver Argento’s wholly unique vision here.

It’s such a singular moment in a career comprised of singular moments that I just want to stand up and applaud every single time I rewatch this scene in Opera. It’s a moment that is so unapologetically Dario Argento that I just love it so damn much and there’s just no one else out there who would craft such a moment.

All I wanted was your love.

At the heart of Opera is a pattern of trauma, in the form of everything that Betty has endured and with Santini, too. While he’s most definitely a villain, and Argento never once tries to excuse his behavior, we learn that his warped fascination with Betty came about because of the emotional and sexual manipulation he experienced at the hands of her mother decades prior. She demanded Santini carry out heinous murders as a means of satisfying her cruel desires, and eventually it drove him to ultimately murder her in the end.

It’s also worth noting that I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it’s Macbeth that is the story featured in Opera, as both Santini and the titular character in Shakespeare’s story both suffer from PTSD, and the condition causes them both to lash out in very destructive ways, ultimately leading them towards a tragic fate in the end. It’s an audacious move to take on two of the greatest stories that examine the lingering effects of psychological damage, but somehow Argento makes it look nearly effortless here.

It’s unclear whether or not Santini continued to indulge in these murderous activities prior to the events of Opera, but he does admit in the finale that once he laid eyes on Betty, it awakened something deep inside him. He sees the young singer as the reincarnation of her mother, and that vision fueled his barbaric rampage that culminates in a fiery finale where we’re led to believe that Santini wants to die at the hands of Betty, but it’s eventually revealed that the inspector faked his death and has escaped.

The epilogue catches up with Betty and Marco in the idyllic Swiss Alps, licking their wounds after the hellish events that Santini put everyone through. While the cinematography and natural setting would indicate that they’re both now finally safe, we horror fans know that looks can be deceiving. Somehow, Santini has been able to track Betty down, and he sets out to put an end to his torment once and for all. After a well-meaning Marco is repeatedly stabbed, Betty is able to turn the tables on Santini, manipulating him into following her, only for the killer to be captured by a group of policemen who happen to be in the area.

The final moments of Opera, with Betty sitting in the grass as she gets closure on the trauma that had been haunting her for so long, are so important because they show that she’s finally reclaimed her life after all this time. Betty no longer will allow herself to be exploited, and she has finally broken free from the twisted legacy of her mother as well. This ordeal has changed her, for the better, and Betty is no longer a victim willing to serve as a spectator to anyone’s manic agenda. Opera provides a beautiful and powerful conclusion for Betty’s story, one that feels wholly satisfying, proving that it is possible to find peace even after you’ve been to hell and back.

This was never closure that we got to see with Christine, as in the original Phantom of the Opera story, she elopes with Raoul. Here, Betty gets to reclaim her life as she no longer has to live her life on anyone else’s terms which is pretty cool (and something we see with a lot of Argento’s female protagonists, which again, is probably why I’m such a big fan of his work as a whole).